Shadows Project 2022 / Over View

Project Statement /Description

The University of Montana Print Department Matrix Press Team Director James Bailey, faculty member Jason Clark, and students Dagny Walton, Tanya Gardner, and Crystal McCallie produced the Shadow Series of 10 site-specific prints by invited artist Corwin Clairmont.

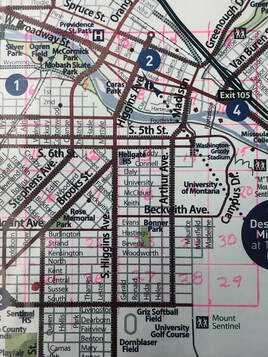

10 random sites were selected within a one square mile area of Missoula. The one square mile encompassed the University of Montana Campus and surrounding areas.

Using a Missoula City Map, a one square mile area, including the University of Montana campus, was outlined on the map. This outlined square mile was gridded into 30 squares of equal size. Each square was given a number from one to thirty. Thirty pieces of paper numbered from 1 to 30 were then placed in a container and at random, 10 pieces of paper were drawn out. These 10 pieces of paper determined the 10 sites to be visited. A red dot was placed on the selected map squares to be more place specific while at the site.

Clear plastic sheets were attached to 10 window screen frames. At each site, drawings were made on the clear plastic sheets using opaque markers and paint. Walking around the site, items of interest were found that would represent and document the site. As a collaborative effort of Matrix Press team member’s faculty Jason Clark, and U of M students Crystal McCallie, Tanya Gardner and myself, composed, and drew the representative images on the clear plastic sheets. These clear plastic sheet drawings were then used to create 10 photo silkscreens of the 10 random sites. A QR code was printed on thin dyed paper and Collaged on each print giving specific information about the 10 selected sites, artwork development, and concepts.

Artist Statement

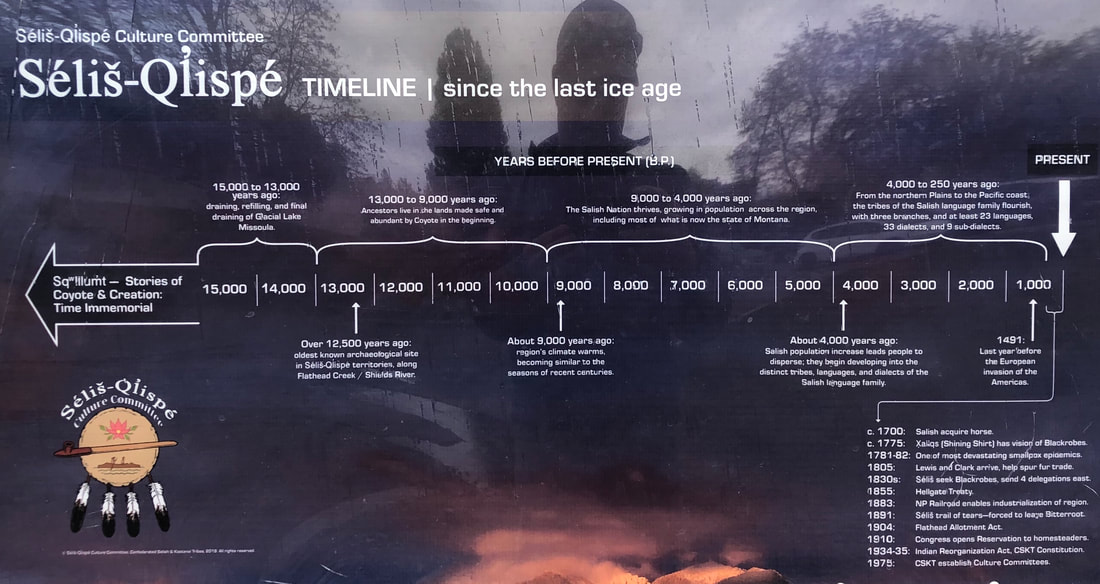

An enrolled member of the Confederated Salish & Kootenai Tribes, I chose to do a series of 10 random site-specific prints in the Missoula area by exploring these sites and documenting through photographs and on site drawings representative items found at each of these sites. The one square mile area chosen is an important cultural and traditional food gathering place of the Salish Tribal People for over10, 000 years. This area contained abundant bitterroot plants in the once open grounds, and bull trout found in the Clark Fork River. By visiting these sites I wanted to remember our Salish ancestors as well as the plants, and animals now displaced by the Missoula community and University. I also wanted to document changes that have occurred or what may have remained the same. Education is high on what is important to our tribal communities and although the bitterroot is no longer harvested on the one square mile land area, it is hoped that higher education opportunities will equally contribute to the positive economy, cultural strength, health and good future of our tribal people and for those yet to come.

There are different concepts, symbols, and images used in the prints. The collaborative nature of the artwork is important as it pertains to the need to depend on one another to accomplish objectives. It promotes consideration of one another’s ideas and suggestions. We learn more when this happens and are better able to understand the need for diversity to survive and grow. Collaboration is about compromise and respect of others and their ideas. The random selection of each site reinforces the concept that each place is important and should be respected as it effects or impacts the great circle or whole of life. The shadow images represent the animals and ancestors who have been displaced or are not with us physically, who have walked this landscape. The shadow is something that you can’t touch or hold, much like the spirits of our ancestors whose silent presence we can’t touch but remain with us. The two-headed arrow, a highway symbol of caution, was cut from each print. It is a reminder that we need to stop and choose which direction we are to take. We are at a critical point in our climate of global warming that we no longer have the flexibility of making wrong choices. - Corwin Clairmont

The University of Montana Print Department Matrix Press Team Director James Bailey, faculty member Jason Clark, and students Dagny Walton, Tanya Gardner, and Crystal McCallie produced the Shadow Series of 10 site-specific prints by invited artist Corwin Clairmont.

10 random sites were selected within a one square mile area of Missoula. The one square mile encompassed the University of Montana Campus and surrounding areas.

Using a Missoula City Map, a one square mile area, including the University of Montana campus, was outlined on the map. This outlined square mile was gridded into 30 squares of equal size. Each square was given a number from one to thirty. Thirty pieces of paper numbered from 1 to 30 were then placed in a container and at random, 10 pieces of paper were drawn out. These 10 pieces of paper determined the 10 sites to be visited. A red dot was placed on the selected map squares to be more place specific while at the site.

Clear plastic sheets were attached to 10 window screen frames. At each site, drawings were made on the clear plastic sheets using opaque markers and paint. Walking around the site, items of interest were found that would represent and document the site. As a collaborative effort of Matrix Press team member’s faculty Jason Clark, and U of M students Crystal McCallie, Tanya Gardner and myself, composed, and drew the representative images on the clear plastic sheets. These clear plastic sheet drawings were then used to create 10 photo silkscreens of the 10 random sites. A QR code was printed on thin dyed paper and Collaged on each print giving specific information about the 10 selected sites, artwork development, and concepts.

Artist Statement

An enrolled member of the Confederated Salish & Kootenai Tribes, I chose to do a series of 10 random site-specific prints in the Missoula area by exploring these sites and documenting through photographs and on site drawings representative items found at each of these sites. The one square mile area chosen is an important cultural and traditional food gathering place of the Salish Tribal People for over10, 000 years. This area contained abundant bitterroot plants in the once open grounds, and bull trout found in the Clark Fork River. By visiting these sites I wanted to remember our Salish ancestors as well as the plants, and animals now displaced by the Missoula community and University. I also wanted to document changes that have occurred or what may have remained the same. Education is high on what is important to our tribal communities and although the bitterroot is no longer harvested on the one square mile land area, it is hoped that higher education opportunities will equally contribute to the positive economy, cultural strength, health and good future of our tribal people and for those yet to come.

There are different concepts, symbols, and images used in the prints. The collaborative nature of the artwork is important as it pertains to the need to depend on one another to accomplish objectives. It promotes consideration of one another’s ideas and suggestions. We learn more when this happens and are better able to understand the need for diversity to survive and grow. Collaboration is about compromise and respect of others and their ideas. The random selection of each site reinforces the concept that each place is important and should be respected as it effects or impacts the great circle or whole of life. The shadow images represent the animals and ancestors who have been displaced or are not with us physically, who have walked this landscape. The shadow is something that you can’t touch or hold, much like the spirits of our ancestors whose silent presence we can’t touch but remain with us. The two-headed arrow, a highway symbol of caution, was cut from each print. It is a reminder that we need to stop and choose which direction we are to take. We are at a critical point in our climate of global warming that we no longer have the flexibility of making wrong choices. - Corwin Clairmont

Additional background information:

Nłʔay / Missoula area place-names:

http://www.csktsalish.org/index.php/ethnogeography/missoula-area

http://www.csktsalish.org/index.php/ethnogeography/missoula-area

Séliš-Ql̓ispé Territories:

http://www.csktsalish.org/index.php/ethnogeography/territories

http://www.csktsalish.org/index.php/ethnogeography/territories

| Treaty of Hell Gate_1855.pdf | |

| File Size: | 86 kb |

| File Type: | |

Salish Removal to the Jocko Valley

In the Hellgate Treaty of 1855, Xwełx̣ ƛcin (Plenty Horses or Chief Victor) and the Salish people insisted on staying in their homeland, the Bitterroot Valley. The treaty

guaranteed the Bitterroot for them unless the President decided, on the basis of a survey, that the Flathead Reservation was "better adapted to the wants of the Flathead Tribe." Although the required survey was never conducted, President Ulysses S. Grant declared in 1871 that the Salish had to be "removed" to the Reservation. By this time, Słmxe Qwoxqeys (Claw of the Small Grizzly, or Chief Charlot) had succeeded his father, Xwełxƛcin, as Head Chief, but he stuck to Xwełxƛcin's position of peacefully resisting removal from the Bitterroot. So when the U.S. sent officials to Montana in 1872, Słmx̣ e Q̓ wox̣ qeys said this was where the bones of his ancestors were buried, and he would not leave. Congress never knew of the Chief's refusal to sign, however, because the negotiator, future U.S. President James Garfield, forged the "x" mark of Słmx̣ e Q̓wox̣ qeys onto the agreement. Non-Indians called Słmx̣ e Q̓wox̣ qeys a treaty breaker until this outrageous forgery was proven to be true by Senator G.G. Vest in 1883.

However, two sub-chiefs, Arlee and Ninepipes, decided it would be best to move. They left the Bitterroot Valley in 1873, accompanied by a few families, and moved to the Jocko. The U.S. treated Arlee as Head Chief, giving him a house and a small stipend, which only deepened the anger and distrust of Słmx̣ e Q̓wox̣ qeys toward the Government. Then the Northern Pacific Railroad was constructed thru the Reservation in 1883, they named the depot in the Jocko "Arlee," and this remained the name of the town, which got its first post office in 1901.

The majority of the Salish, meanwhile stayed in their ancestral Bitterroot Valley under the leadership of Słmx̣ e Q̓wox̣ qeys. White settlers began to crowed in around them, even though these incursions were not allowed by the terms of the Treaty. As a result, the tribe became more poor. Nevertheless, when Chief Joseph's band of Nez Perce came through the valley during the 1877 war, the Salish refused to join their long-time friends and relations, and instead defended the settlements. Despite this, non-Indians and the Government only increased pressures on the Salish to leave the Bitterroot, which was considered some of the best agricultural land in Montana. Słmx̣ e Q̓ wox̣ qeys repeatedly refused to move.

After the Missoula & Bitterroot Valley Railroad was built in 1888, white settlement began to increase more rapidly, and in November 1889, faced with worsening conditions for his people, Chief Charlot finally agreed to move. He secured guarantees of housing and other material help for the people once the relocated to the Reservation. Told that they would be moving right away, the Salish did not plant props in the spring of 1890. Congress appropriated no funds for the removal, so the people remained in the valley--but now without the food they would have normally raised. The same ting happened the next year, as Congress continued its patrons malign neglect. Throughout 1890 and 1891 Salish people sold their stoves and other house hold belongings in their struggle to get enough to eat. Finally in october 1891, General Henry B. Carrington and a contingent of troops from Fort Missoula roughly uprooted the people from Stevensville area and marched them north to the Reservation.

Many elders, including Sophie Moiese and Mary Ann Combs have related the sadness of the journey and the rough way people were treated by troops. One woman, Mrs. Lumpry, fell off her horse and broke her hip, and was crippled for life. Mrs Combs recalled that after the two day journey, the people camped near Evaro called Nłesletkw (Two Creeks). The people pulled them selves together, and led by young men riding out ahead on their horses, the Salish came into the Jocko Valley. A large group of Pend d'orville and other tripbal people awaited them at the Jocko church, and welcomed them to the Reservation. It is said the Salish settled at the southern end of the Reservation because they did not wish to move any further north than they had to. So the homes of Słmx̣ e Q̓ wox̣ qeys, Sam Resurrection, Sophie Moiese, the Vanderburgs and many others were spread between Snłiʔoyčn (Evaro), Snłaʔcná (Schley), Nłqá (Arlee) and łqwqwʔú (Valley Creek). Some Salish families, notably the Pierres, moved back to the Bitterroot after 1891.

Despite the pain and loss of removal, the Salish quickly rebutlt their lives on the Reservation, establishing many successful family farming and cattle operations. They did this even thou the Government reneged on many of its promises of help.

Ten years after the removal the Salish and the Governments solemn promise that the Reservation would always be a protected home for the people, free from harassment, congress passed the law that would open the Flathead Reservation to white settlement. Tribal members, including Chief Charlot and Sam Resurrection, repeatedly protested this law, but to no avail. In 1910, the homesteaders poured in to the Reservation, taking much of the best land. The Flathead Irrigation Project was built, often over pre existing Indian built ditches, and suddenly Tribal farmers had to pay for water they had always used for free. Many small operation had produced food only for subsistence needs, and families couldn't pay these new fees. Many Tribal allotments were sold to non- Indians before the Allotment Act was cancelled in 1934.

The salish survived all this, and Arelee today is the home to a vibrant Salish community. Salish homes are found throughout the area. In the arlee schools, Salish language classes have been taught for many years now to the many Salish students. The Vanberberg Culture Camp at Valley Creek was founded by Agnes Vanderburg in 1974 and run by her until her death in 1989. Th camp is now run by her daughter Lucy and son Victor, and was opened to all interested people from June thru August for hunting, fishing, camping, solitude and gathering of foods and medicines.

-Selis-Qlispe Culture Committee

In the Hellgate Treaty of 1855, Xwełx̣ ƛcin (Plenty Horses or Chief Victor) and the Salish people insisted on staying in their homeland, the Bitterroot Valley. The treaty

guaranteed the Bitterroot for them unless the President decided, on the basis of a survey, that the Flathead Reservation was "better adapted to the wants of the Flathead Tribe." Although the required survey was never conducted, President Ulysses S. Grant declared in 1871 that the Salish had to be "removed" to the Reservation. By this time, Słmxe Qwoxqeys (Claw of the Small Grizzly, or Chief Charlot) had succeeded his father, Xwełxƛcin, as Head Chief, but he stuck to Xwełxƛcin's position of peacefully resisting removal from the Bitterroot. So when the U.S. sent officials to Montana in 1872, Słmx̣ e Q̓ wox̣ qeys said this was where the bones of his ancestors were buried, and he would not leave. Congress never knew of the Chief's refusal to sign, however, because the negotiator, future U.S. President James Garfield, forged the "x" mark of Słmx̣ e Q̓wox̣ qeys onto the agreement. Non-Indians called Słmx̣ e Q̓wox̣ qeys a treaty breaker until this outrageous forgery was proven to be true by Senator G.G. Vest in 1883.

However, two sub-chiefs, Arlee and Ninepipes, decided it would be best to move. They left the Bitterroot Valley in 1873, accompanied by a few families, and moved to the Jocko. The U.S. treated Arlee as Head Chief, giving him a house and a small stipend, which only deepened the anger and distrust of Słmx̣ e Q̓wox̣ qeys toward the Government. Then the Northern Pacific Railroad was constructed thru the Reservation in 1883, they named the depot in the Jocko "Arlee," and this remained the name of the town, which got its first post office in 1901.

The majority of the Salish, meanwhile stayed in their ancestral Bitterroot Valley under the leadership of Słmx̣ e Q̓wox̣ qeys. White settlers began to crowed in around them, even though these incursions were not allowed by the terms of the Treaty. As a result, the tribe became more poor. Nevertheless, when Chief Joseph's band of Nez Perce came through the valley during the 1877 war, the Salish refused to join their long-time friends and relations, and instead defended the settlements. Despite this, non-Indians and the Government only increased pressures on the Salish to leave the Bitterroot, which was considered some of the best agricultural land in Montana. Słmx̣ e Q̓ wox̣ qeys repeatedly refused to move.

After the Missoula & Bitterroot Valley Railroad was built in 1888, white settlement began to increase more rapidly, and in November 1889, faced with worsening conditions for his people, Chief Charlot finally agreed to move. He secured guarantees of housing and other material help for the people once the relocated to the Reservation. Told that they would be moving right away, the Salish did not plant props in the spring of 1890. Congress appropriated no funds for the removal, so the people remained in the valley--but now without the food they would have normally raised. The same ting happened the next year, as Congress continued its patrons malign neglect. Throughout 1890 and 1891 Salish people sold their stoves and other house hold belongings in their struggle to get enough to eat. Finally in october 1891, General Henry B. Carrington and a contingent of troops from Fort Missoula roughly uprooted the people from Stevensville area and marched them north to the Reservation.

Many elders, including Sophie Moiese and Mary Ann Combs have related the sadness of the journey and the rough way people were treated by troops. One woman, Mrs. Lumpry, fell off her horse and broke her hip, and was crippled for life. Mrs Combs recalled that after the two day journey, the people camped near Evaro called Nłesletkw (Two Creeks). The people pulled them selves together, and led by young men riding out ahead on their horses, the Salish came into the Jocko Valley. A large group of Pend d'orville and other tripbal people awaited them at the Jocko church, and welcomed them to the Reservation. It is said the Salish settled at the southern end of the Reservation because they did not wish to move any further north than they had to. So the homes of Słmx̣ e Q̓ wox̣ qeys, Sam Resurrection, Sophie Moiese, the Vanderburgs and many others were spread between Snłiʔoyčn (Evaro), Snłaʔcná (Schley), Nłqá (Arlee) and łqwqwʔú (Valley Creek). Some Salish families, notably the Pierres, moved back to the Bitterroot after 1891.

Despite the pain and loss of removal, the Salish quickly rebutlt their lives on the Reservation, establishing many successful family farming and cattle operations. They did this even thou the Government reneged on many of its promises of help.

Ten years after the removal the Salish and the Governments solemn promise that the Reservation would always be a protected home for the people, free from harassment, congress passed the law that would open the Flathead Reservation to white settlement. Tribal members, including Chief Charlot and Sam Resurrection, repeatedly protested this law, but to no avail. In 1910, the homesteaders poured in to the Reservation, taking much of the best land. The Flathead Irrigation Project was built, often over pre existing Indian built ditches, and suddenly Tribal farmers had to pay for water they had always used for free. Many small operation had produced food only for subsistence needs, and families couldn't pay these new fees. Many Tribal allotments were sold to non- Indians before the Allotment Act was cancelled in 1934.

The salish survived all this, and Arelee today is the home to a vibrant Salish community. Salish homes are found throughout the area. In the arlee schools, Salish language classes have been taught for many years now to the many Salish students. The Vanberberg Culture Camp at Valley Creek was founded by Agnes Vanderburg in 1974 and run by her until her death in 1989. Th camp is now run by her daughter Lucy and son Victor, and was opened to all interested people from June thru August for hunting, fishing, camping, solitude and gathering of foods and medicines.

-Selis-Qlispe Culture Committee

Matrix Press printing processes

100 sheets of Arnheim paper were dyed using Rit dye and acrylic paint creating a variety of background color and design effects. A split fountain or rainbow role colors were printed on the paper. Stencils of bitterroot plants, bull trout, animal, insects and geometric symbols were used during the printing process. The 10 random site drawings were then silkscreen printed over the dyed and relief rolled paper. A large shadow image of coyote, bear, eagle and human being expressing a peace sign, was screen printed over a large portion of the images on the prints.

A two-headed arrow, a common traffic symbol shape seen on traffic warning signs at T highway intersections, was cut out of each print. These cutouts were then taken back to the 10 print’s respective sites and left at those sites. In giving something back, the two-headed arrow paper cutouts and prints themselves, became a physical part of the landscapes site. 10 QR codes were developed by Jim Baily for each 10 Shadow series prints. The QR code was silkscreen printed on dyed thin paper and then collaged onto the respective print.

100 sheets of Arnheim paper were dyed using Rit dye and acrylic paint creating a variety of background color and design effects. A split fountain or rainbow role colors were printed on the paper. Stencils of bitterroot plants, bull trout, animal, insects and geometric symbols were used during the printing process. The 10 random site drawings were then silkscreen printed over the dyed and relief rolled paper. A large shadow image of coyote, bear, eagle and human being expressing a peace sign, was screen printed over a large portion of the images on the prints.

A two-headed arrow, a common traffic symbol shape seen on traffic warning signs at T highway intersections, was cut out of each print. These cutouts were then taken back to the 10 print’s respective sites and left at those sites. In giving something back, the two-headed arrow paper cutouts and prints themselves, became a physical part of the landscapes site. 10 QR codes were developed by Jim Baily for each 10 Shadow series prints. The QR code was silkscreen printed on dyed thin paper and then collaged onto the respective print.